Iran Hostage Crisis

CASE CONCERNING UNITED STATES DIPLOMATIC AND CONSULAR STAFF IN TEHRAN

(UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. IRAN)

24 May 1980

ISSUES OF LAW

- Jurisdiction of the Court

- Optional Protocols to Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963 on Diplomatic and Consular Relations

- 1955 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations and Consular Rights (USA/Iran)

- Provision for recourse to Court unless parties agree to “settlement by some other pacific means”

- Right to file unilateral Application

- Whether counter-measures a bar to invoking Treaty of Amity

- State responsibility for violations of Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963 on Diplomatic and Consular Relations

- Phase One

- Action by persons not acting on behalf of State

- Non-imputability thereof to State

- Breach by State of obligation of protection (12,13,14)

- International obligations under the Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963

- Breach of the 1955 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights

- Obligations under general international law

- Conclusion of Phase One

- Phase Two

- Subsequent decision to maintain situation so created on behalf of State and use of situation as means of coercion

- Questions of special circumstances as possible justification of conduct of State

- Remedies provided for by diplomatic law for abuses

- Cumulative effect of successive breaches of international obligations

- The incursion into the territory of Iran made by United States military units

1. Jurisdiction of the Court

Article 53 of the Statute requires the Court, before deciding in favor of an Applicant’s claim, to satisfy itself that it has jurisdiction.

2. Optional Protocols to Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963 on Diplomatic and Consular Relations

The Optional Protocols accompanying the Vienna Conventions of 1961 on Diplomatic Relations and of 1963 on Consular Relations manifestly provide a possible basis for the Court’s jurisdiction.

The principal claims of the United States relate essentially to alleged violations by Iran of its obligations to the United States under the Vienna Conventions of 1961 on Diplomatic Relations and of 1963 on Consular Relations.

With regard to these claims, the United States evoked Article I of the Optional Protocols concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes which accompanies these Conventions as the basis for the Court’s jurisdiction.

Both Iran and United States are parties to the Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963, as well as to their accompanying Protocols concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes, and in each case without any reservation. Additionally, the Iranian Government has not maintained in its communications to the Court that two Vienna Conventions and Protocols are not in force between Iran and the United States. Accordingly, the Protocols manifestly provide a possible basis for the Court’s jurisdiction.

3. 1955 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations and Consular Rights (USA/Iran)

The United States also presents claims in respect of alleged violation by Iran of Article II of the Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights of 1955 between United States and Iran.

The Order of 15 December 1979 indicating provisional measures did not find it necessary to enter into the question whether the 1955 Treaty might also have provided a basis for the exercise of its jurisdiction in the present case since the claims of the United States under this Treaty overlap in considerable measure with its claims under the two Vienna Conventions.

However, the Court considers that Treaty has importance in regard to the claims of the two private individuals said to be held hostage in Iran. The 1955 Treaty remains applicable between Iran and the United States, despite that the machinery for the effective operation of the 1955 Treaty had been impaired by reason of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Given the very purpose of a treaty of amity, it would be incompatible with the whole purpose of the 1995 Treaty if recourse to the Court were to be found not open to the parties at the moment when such recourse was most needed.

4. Provision for recourse to Court unless parties agree to “settlement by some other pacific means”

Article XXI of the 1995 Treaty provides:

“Any dispute between the High Contracting Parties as to the interpretation or application of the present Treaty, not satisfactorily adjusted by diplomacy, shall be submitted to the International Court of Justice, unless the High Contracting Parties agree to settlement by some other pacific means”

The immediate and total refusal of the Iranian authorities to enter into any negotiations with the United States excluded any question of an agreement to have recourse to “some other pacific means” for the settlement of the dispute. Consequently, the United States was free to invoke its provisions for the purpose of referring its claims against Iran under 1955 Treaty to the Court.

5. Right to file unilateral Application

While the 1955 Treaty does not provide in express terms that either party may bring a case to the Court by unilateral application, it is evident that this is what the parties intended.

Provisions drawn in similar terms are very common in bilateral treaties of amity and the intention of the parties in accepting such clauses is clearly to provide for such a right of unilateral recourse to the Court, in the absence of agreement to employ some other pacific means of settlement.

6. Whether counter-measures a bar to invoking Treaty of Amity

The United States took several measures in response to what she believes to be grave and manifest violations of international law by Iran.

In terms of whether the counter-measures bar the United States from invoking Treaty of Amity, the Court asserts that in any event, any alleged violation of the Treaty by either party could not have the effect of precluding that party from invoking the provisions of the Treaty concerning pacific settlement of disputes.

7. State responsibility for violations of Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963 on Diplomatic and Consular Relations

The events which are the subject of the United States’ claims fall into two phases which it will be convenient to examine separately.

First, the Court must determine how far, legally, the acts in question may be regarded as imputable to the Iranian State. Secondly, the Court must consider their compatibility with the obligations of Iran under treaties in force or under any other rules of international law that may be applicable.

8. Phase One

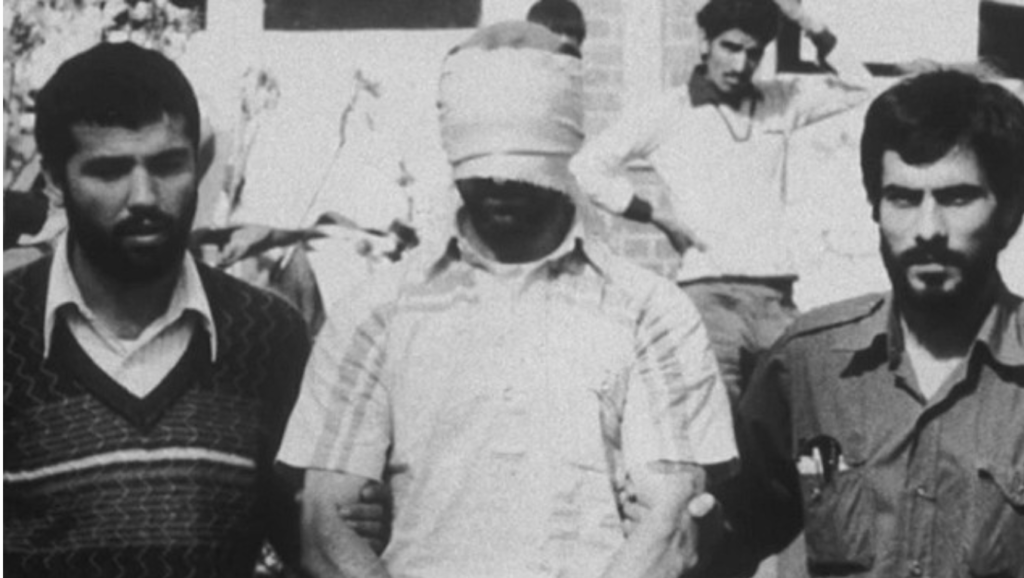

The first of these phases covers the armed attack on the United States Embassy and Consulates by militants, the overrunning of its premises, the seizure of its inmates as hostages, the appropriation of its property and archives and the conduct of the Iranian authorities in the face of those occurrence.

9. Action by persons not acting on behalf of State

The militants’ conduct might be considered as itself directly imputable to the Iranian State only if it were established that the militants acted on behalf of the State.

However, no suggestion has been made that the militants, when they executed their attack on the Embassy and Consulates, had any form of official status as recognized agents or organs of the Iranian State, nor were them charged by some competent organ of the Iranian State.

The information before the Court does not suffice to establish with the requisite certainty the existence at that time of such a link between the militants and any competent organ of the state.

10. Non-imputability thereof to State

The religious leader of the country, the Ayatollah Khomeini, had made several public declarations inveighing against the United States, which would appear he was inciting hatred by the supporters of revolution.

In the view of the Court, however, it would be going too far to interpret such general declarations of the Ayatollah Khomeini to the people as amounting to an authorization from the State to undertake the specific operation of invading and seizing the United States Embassy and Consulates.

11. Breach by State of obligation of protection

The initiation of the attack on the United States Embassy and Consulates cannot be considered as in itself imputable to the Iranian State does not mean that Iran is, in consequence, free of any responsibility in regard to those attacks.

12. International obligations under the Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963

Iranian State’s own conduct was in conflict with its international obligations under the Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963. As a receiving State, Iran has the obligations to take appropriate steps to ensure the protection of the United States Embassy and Consulates, their staffs, their archives, their means of communication and the freedom of movement of the members of their staffs.

The Articles of the Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963 Iran violated include:

- Article 22: the inviolability of the premises of a diplomatic mission.

- Article 29: the person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable, and that he shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention.

- Article 24: the obligation of a receiving State to protect the inviolability of the archives and documents of a diplomatic mission, which are inviolable at any time and wherever they may be.

- Article 25: the obligation of a receiving State to accord full facilities for the performance of the functions of the mission.

- Article 26: the obligation of a receiving State to ensure to all members of the mission freedom of movement and travel in its territory

- Article 27: the obligation of a receiving State to permit and protect free communication on the part of the mission for all official purposes

Analogous provisions are to be found in the 1963 Convention regarding the privileges and immunities of consular missions and their staffs (Art. 31, para. 3, Arts. 40, 33, 28, 34 and 35).

13. Breach of the 1955 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights

The obligations of Iran existing under 1955 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights require the parties to ensure “the most constant protection and security” to each other’s nationals in their respective territories.

So far as concerns the two private United States nationals seized as hostages by the invading militants, that inaction entailed, albeit incidentally, a breach of its obligations under Article II of the 1955 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights.

14. Obligations under general international law

The obligations of the Iranian Government in question are not merely contractual obligations established by the Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963, but also obligations under general international law.

In the opinion of the Court, the failure of the Iranian Government to take appropriate steps either to prevent the attack or stop it before it reached its completion was due to more than mere negligence or lack of appropriate means.

The total inaction of the Iranian authorities on that date in face of urgent and repeated requests for help contrasts very sharply with its conduct on several other occasions of a similar kind, such as the armed attack on 14 February 1979, where a detachment of Revolutionary Guards were sent by the Government to free the Ambassador and his staffs, as well as restore the Embassy. In addition, other invasions or attempted invasions in November 1979 and January 1980 of other foreign embassies in Tehran were speedily terminated. A similar pattern of facts appears in relations to consulates.

15. Conclusion of Phase One

The Court is lad inevitably to conclude, in regard to the first phase of the events which has so far been considered, that on 4 November 1979 the Iranian authorities:

(a) were fully aware of their obligations under the conventions in force to take appropriate steps to protect the premises of the United States Embassy and its diplomatic and consular staff from any attack and from any infringement of their inviolability, and to ensure the security of such other persons as might be present on the said premises;

(b) were fully aware, as a result of the appeals for help made by the United States Embassy, of the urgent need for action on their part;

(c) had means at their disposal to perform their obligations;

(d) completely failed to comply with these obligations;

Similarly, the Court is led to conclusion that Iranian authorities were equally aware of their obligations to protect the United States Consulates at Tabriz and Shiraz, and of the need for action on their part, and similarly failed to use the means which were at their disposal to comply with their obligations.

17. Phase Two

The second phase of the events which are the subject of the United States’ claims comprises the whole series of facts which occurred following the completion of the occupation of the United States Embassy by militants, and the seizure of the Consulates at Tabriz and Shiraz.

After the completion of violation of the abovementioned Treaties and general international law by militants, the action required of the Iranian Government by international obligations was at once to make every effort, and to take every step, to bring these flagrant infringements to a speedy end, to restore the premises to United States control, and offer reparation for the damage.

No such steps was, however, taken by the Iranian authorities.

18. Subsequent decision to maintain situation so created on behalf of State and use of situation as means of coercion

The official government approval was issued by a decree on 17 November 1979 by the Ayatollah Khomeini. His decree began with the assertion that the American Embassy was “a center of espionage and conspiracy” and that “those people who hatched plots against our Islamic movement in that place do not enjoy international diplomatic respect”

He went on to declare that the premises of the Embassy and the hostages would remain as they were until the United States had handed over the former Shah for trial and returned his property to Iran.

The result of that policy was fundamentally to transform the legal nature of the situation created by occupation of the Embassy and the detention of its diplomatic and consular staffs as hostage.

The approval by the Ayatollah Khomeini and other organs of the Iranian State, and the decision to perpetuate them, translated continuing occupation of the Embassy and detention of the hostages into acts of that States.

19. Questions of special circumstances as possible justification of conduct of State

The Court cannot overlook the fact that the conduct of the Iranian Government might be justified by the existence of special circumstances.

The Iranian authorities took the position that the United States’ Application could not be examined by the Court divorced from its proper context, which he insisted was “the whole political dossier of the relations between Iran and the United States over the past 25 years”

The Court, however, finds that no circumstances exist in the case which are capable of negating the fundamentally unlawful character of the conduct pursued by the Iranian State on 4 November 1979 and thereafter since the alleged criminal activities and espionage and interference in Iran are unsupported by evidence furnished by Iran before the Court.

20. Remedies provided for by diplomatic law for abuses

In any case, even the alleged criminal activities of the United States in Iran could be considered as having been established, the Court is unable to accept that they could be regarded as constituting a jurisdiction of Iran’s conduct thus a defense to the United States claims in the case.

This is because diplomatic law itself provides the necessary means of defense against, and sanction for, illicit activities by member of diplomatic or consular mission, such as declaration of persona non grata or breaking off diplomatic relationship, whereas the Iranian Government did not recourse to the normal and efficacious means at its disposal, but resorted to coercive action.

21. Cumulative effect of successive breaches of international obligations

The Court finds that Iran, by committing successive and continuing breaches of the obligations, has incurred responsibility towards the United States.

As to the consequences of this finding, it clearly entails an obligation on the part of the Iranian State to make reparation for the injury thereby caused to the United States. Since Iran’s breaches of its obligations are still continuing, the form and amount of such reparation cannot be determined at the date when judgement was made.

22. The incursion into the territory of Iran made by United States military units

The Court was in course of preparing the judgement adjudicating upon the claims of the United States against Iran when the incursion into the territory of Iran made by United States military units on 24-25 April 1980 took place.

Even though the Court considered the operation is of a kind calculated to undermine respect for the judicial process in international relations, neither the question of legality of the operation nor possible responsibility is before the court. This question can have no bearing on the evaluation of the conduct of Iranian Government. It follows that the findings reached by the Court in this Judgement are not affected by that operation.